Lake Mungo and its past inhabitants

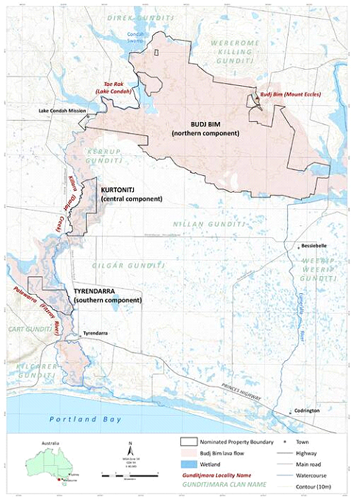

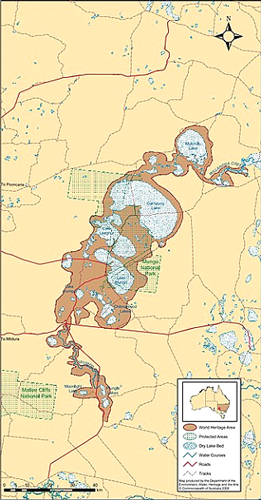

It is hard to appreciate when driving across the bed of Lake Mungo in semi-arid, southwestern New South Wales that this used to be up to 15 metre deep freshwater and spread over 200 square kilometre with an environment that provided favourable living conditions for the predecessors of the three local Aboriginal ‘tribes’. The Barkindji (Parkantiji), Nylampaa (Nglyampee), and Mutthi claim Willandra Lakes, including Lake Mungo, as their Traditional Land and meeting place.

A response of rivers flowing over flat riverine plains is the development of anabranches (river offshoot channels), long waterholes and billabongs. In the past Willandra Creek was the longest but not the only Lachlan River off-shoot and behaved as a river anabranch that flowed via the Willandra Lakes, including Lake Mungo, and eventually discharged into the Murray River. Today this creek is still a branch off the Lachlan River but only carries water short distances when the river floods.

The warm wet pre ice age period favoured a wide variety of plant growth, not the arid-adapted species we see today, and consequently there was a wide range of animals for food both on land and in the water for human consumption. Food sources would have included plant products like fruits, seeds, leaf and tubers and those from animals such as kangaroo, emu, reptiles, water birds and fish, and the collection of birds eggs, crayfish and mussels.

Map of the Willandra Lakes Region showing the World Heritage Area

Boundaries. Lake Mungo is in the middle of the chain of lakes.

From Wikipedia, 2020

Following assessment of many different date-measuring techniques (eg radio-carbon dating and optically stimulated luminescence (OSL)) from this burial site, a multi-disciplinary committee of archaeologists, national park personnel and indigenous Australians has assessed the male body to be older than that of the cremated female. In 2015, following requests from the Mungo National Park Traditional Owners, the skeletal remains were locked away and stored at the National Museum and in 2017 they returned to Lake Mungo for reburial.

Visitors to Mungo National Park see other evidence of past Aboriginal occupation by Indigenous guides including stone tools, hearth sites, middens and to hear about cultural practices. It is also possible to visit the woolshed and see other remains of the rural properties Mungo and Zanci that once operated here. Inside the Interpretation Centre visitors can also read about the history of the park including the gigantic Zygomaturus. This is an herbivorous megafauna species that grazed around the Willandra Lakes and became extinct about 33,000 to 37,000 ya.

However, lake levels started to drop by 40,000 ya, with increasing fluctuation in their levels, and by the time the last ice age reached its maximum, 22,000 – 18,000 ya, the freshwater flows had stopped and the average temperatures had dropped by 6 -9 Celsius degrees. Willandra Lakes had dried up and in so doing had accumulated gypsum, crystallised from the evaporated water, on their surfaces and their Aboriginal population had dispersed.

Most of the evidence for human occupation in the Lake Mungo area is derived from artifacts and burial sites that date from the period 50,000 – 25,000 ya prior to the recent ice age, with one major exception. In 2003 there was the discover of many 100s of footprints along 25 individual tracks in mud that was dated from 20,000 ya. These have been rated as Australia’s oldest and only Pleistocene footprints. While most of the prints were human there were some marsupial and emu tracks in the mix.

In 1969 Jim Bowler, a geomorphologist from University of Melbourne, had been studying the crescent shaped dune (a lunette) found on the north and eastern shore of Lake Mungo and chanced upon human skeletal remains exposed by dune erosion. The cremated crushed bones were those of a female. This ceremonial burial took place about 42,000 ya and, to date, this is the oldest cremation known. In 1974 Jim also found the grave site of a man also revealed by wind erosion of the dune. This body had been buried with his arms crossed and covered with red ochre, which was assessed as a ceremonial material that had been sourced from 200 km away.

The Fascinating Lunette

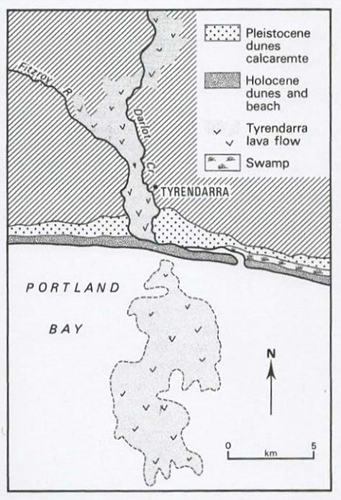

The largest and most prominent feature in the National Park is connected to the eroding lunette on the north eastern side of the lakebed. Lunettes are crescent shaped sand dunes formed on the edge of lake and like most dunes result from the accumulation of wind-blown sediments. Prior to the introduction of rabbits and sheep the lunette maintained its natural vegetation cover and its original shape.

Beginning in 1864, stock grazing began denuding the area and there was the added problem of plant destruction and soil disturbance by rabbits that opened the lunette to wind and water erosion. Today feral goats accentuate the problems of the past. The eventual exposure of the lunette by erosion has revealed its make-up and its various layers as distinguished by the colour, soil texture and position of the remaining sediments.

Eroded lunette with patch of the Gol Gol unit (foreground) and larger mounds of the Mungo unit.

The Lake Mungo lunette was shaped by south-westerly winds and originally, there was a continuous 24 km long, 20 m high ridge capping most of the lunette. Geomorphological and archaeological studies have determined that the lunette was formed on this eastern and north east side of the lake in three main phases following a full lake some 40,000 ya. In low water periods red dust from the plains mixed with beach sand from the lake which accumulated as low, wind-blown dunes that were stabilised by reed and other natural vegetation when it refilled. However as low water periods became more common after 35,000 ya, the persistent winds sweeping across the exposed floor of the lake were able to pick up dried clay and sand and deposited these above the red sands. This created brownish-grey sandy layers and as they accumulated were stabilised by vegetation.

As good seasons returned water levels rose again but more layers were added during the next low water period.

Geomorphologists named the red sand layer the Gol Gol Unit after one of the oldest local stations and the much thicker brownish-grey sandy layer above it the Mungo Unit.

‘Natural: as an outstanding example representing the major stages in the Earth’s evolutionary history; and as an outstanding example representing significant ongoing geological processes. Cultural: bearing an exceptional testimony to a past civilisation.’

Water erosion and The Walls of China. Lake Mungo